Welcome back, my aspiring hackers!

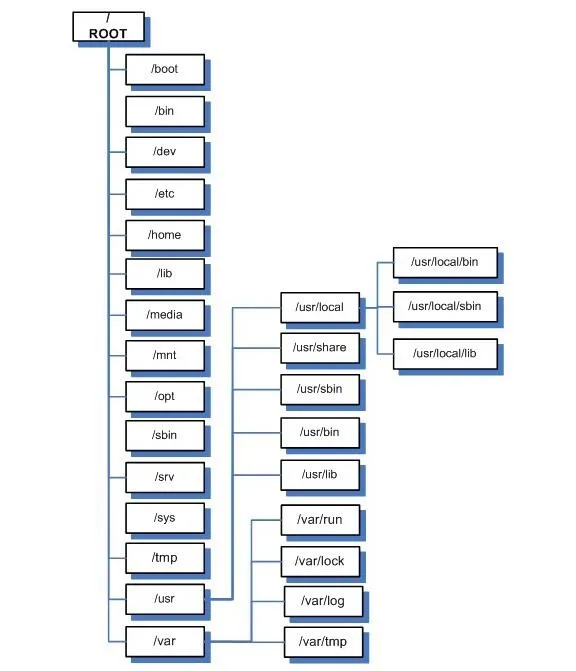

As you have probably discovered by now, the file system in Linux is structured differently from Windows. There are no physical drives—just a logical file system tree with root at the top (yes, I know, roots should be at the bottom, but this is an upside-down tree).

In addition, filenames are often very long and complex with lots of dashes (-), dots (.), and numbers in their names. This can make typing them difficult for those of us with limited keyboard skills (remember, you can always use the tab key to autocomplete if you are in the right directory).

Sometimes we want to simplify the names of a file or we want to link a file in one directory with another in a separate directory. Linux has at least two ways to do this—symbolic (or soft) links and hard links. To understand how these two work and how they are different, we need to delve into some basic background on the Linux file system's internal structure.

Linux File Structure

We know that the Linux file system hierarchical structure is different than the Windows hierarchical structure, but from the inside, Linux's ext2 or ext3 file system is very different from Windows NTFS. Linux stores files at a structural level in three main sections:

- The Superblock

- The Inode Table

- Data Blocks

Let's take brief look at each of these.

Superblocks

The superblock is the section that contains the information about the file system, in general. This includes such things as the number of inodes and data blocks as well as how much data is in each file. It's kind of a overseer and housekeeper of the file system.

Inode Table

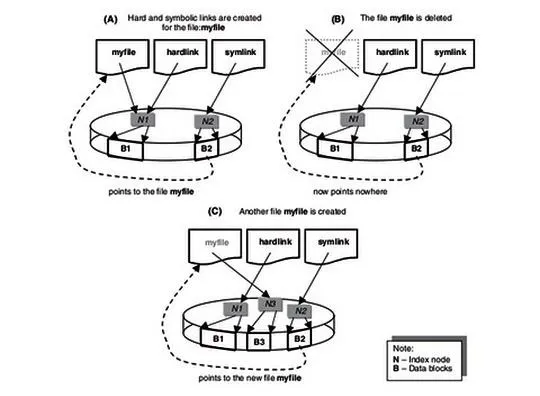

The inode table contains several inodes (information nodes) that describe a file or directory in the file system. Essentally, it is simply a record that describes a file (or directory) with all its critical information such as date created, location, date modified, permissions, and ownership. It does not, however, contain the data in the file.

It's important to understand from a forensic perspective that when a file is deleted, only the inode is removed.

Data Blocks

Data blocks are where the data that is in the file is stored, as well as the file name. Now with that understanding, let's introduce two ways of linking files, the hard link and the soft or symbolic link.

Hard Links

Hard linked files are identical. They have the same size and the same inode. When one hard linked file is modified or changed, it's linked file changes as well. You can hard link a file as many times as you need, but the link cannot cross file systems. They must be on the same file system as they share an inode.

Soft or Symbolic Links

Symbolic or soft links are different from hard links in that they do not share the same inode. A symbolic link is simply a pointer to the other file, similar to links in Windows, and they have different file sizes too. Unlike hard links, symbolic links do NOT need to be on the same file system.

Viewing Links

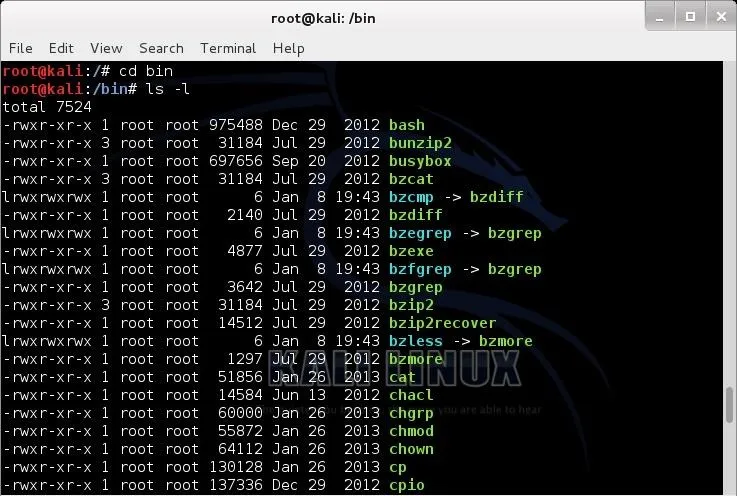

Let's take a look at what links look like in our filesystem on Kali. Let's navigate to the /bin directory. Remember that the /bin directory is just below the root of the file system and contains most the commands that we use on a daily basis in Linux.

kali> cd /bin

Now, let's look at the files in the bin directory.

kali > ls -l

Notice that several files here show an arrow (->) pointing to another file. These are symbolic links. Also, note how small they are. Each is only 6 bytes. That's because they are only pointers, pointing to another file. The data block of the link simply contains the path to the file it is linked to.

When you edit the symbolically linked file, you are actually editing the target file as the symbolic file is only that path to the target file. Hope that makes sense.

Creating Symbolic Links

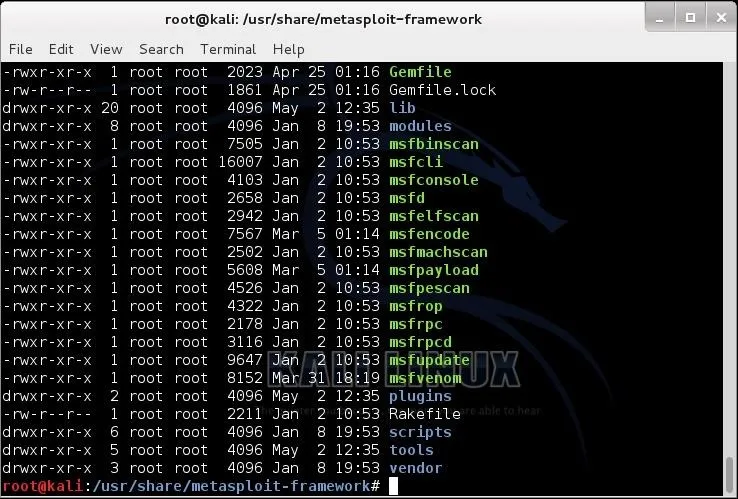

Now, let's create some links. Let's start with symbolic links as they are probably the most common on most people's systems. Although symbolic links can be created anywhere, we will be creating them in the metasploit-framework directory to make starting the msfconsole a touch easier.

Move to the /usr/share/metasploit-framework directory, first.

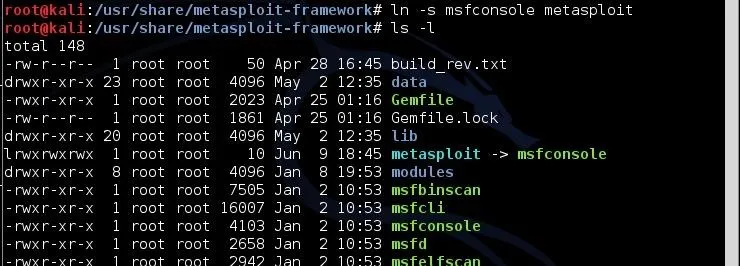

kali > cd /usr/share/metasploit-console

Now, let's take a look at the this directory..

kali > ls -l

To create a symbolic or soft link, we use the ln (link) command with the -s switch (symbolic) and the name of the file we want to link to (the target) and the name of the link we want to create. You can use either relative paths or absolute paths to link the two files.

Usually, when we want to enter the Metasploit console, we type msfconsole, remember? Now, let's say we want to change it so that we can simply type metasploit to enter the console rather having to remember msfconsole. We can link a new file, metasploit, to the old file, msfconsole, so that whenever we type metasploit it links or redirects to msfconsole.

Here is how we would do that.

kali >ln -s msfconsole metasploit

Note how small the symbolic link file, metasploit, is. It's just 12 bytes, because it is only a pointer. A path to the file it is linked to.

Now, to get into the msfconsole, I can type either metasploit or msfconsole and both will take me to the same place—the Metasploit Framework console.

Creating Hard Links

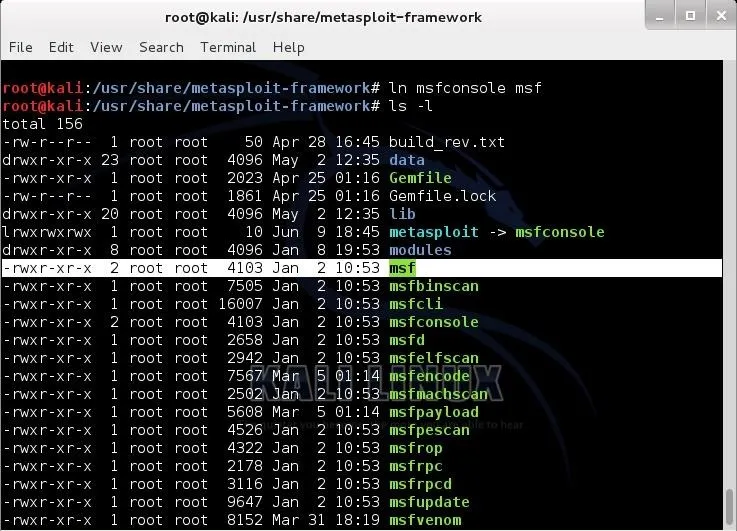

To create a hard link, the syntax is very similar with the exception that we use the ln (link) command without the -s (symbolic) switch, then the existing file to hard link to, and finally, the target file that will be created to the existing file.

Back to our msfconsole example, let's add a hard link between msfconsole to a simpler command, msf. We can do this by typing:

kali > ln msfconsole msf

As you can see above, now we have created a hard link called msf. Remember, hard links share an inode with the linked file, so they are exactly the same size. Notice that our new file, msf, is exactly the same size as msfconsole, 4103 bytes. Now, when we want to invoke (start) the msfconsole, we have the option to type metasploit, msf, and the original msfconsole. All will work equally well.

Comments

Be the first, drop a comment!